It’s tax season! That dreaded time of year where everyone has to sit down, do an accounting of last year’s finances, and figure out what they owe to Uncle Sam. For most, it’s a plug-your-nose-and-get-it-over-with type of chore. A recent survey showed that half of all Americans believe they pay too much in taxes.

This mirrors a sentiment I’ve heard a few times:

“Generally, people hate paying taxes more than they like making money.”

Now, I get that this statement is meant to demonstrate people’s distaste for paying taxes and isn’t necessarily meant to be taken literally, but I’ve had conversations with people who truly feel this way.

It’s easier to hate something that you don’t fully understand, and I’ve spoken with plenty of people who don’t quite understand how federal income taxes work. It’s not really taught anywhere. So, I figured it’d be helpful to briefly go over how income taxes are calculated.

Does an explanation of income tax brackets make it less painful to pay taxes? Of course not. Getting people to not hate paying taxes is an impossible feat. But I do think it’s important to know how our tax system works.

The U.S. has what’s called a progressive tax system, which is just a fancy way of saying that as your income increases, it’ll be taxed at a higher rate. The government decides how much tax you owe by dividing your taxable income into chunks or tax brackets.

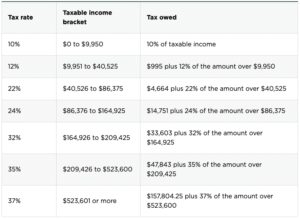

Currently, there are seven tax brackets for ordinary income: 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%. Here are the tax brackets and their corresponding 2021 income ranges for single filers:

If you’re married and file jointly with your spouse, the income ranges are basically double what’s shown above.

The most important thing to understand about tax brackets is that being “in” a certain bracket doesn’t mean you pay that tax rate on all of your income. Each chunk of your income gets taxed at the corresponding rate.

For example:

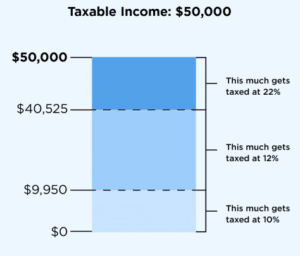

Let’s say you’re a single filer and you had $50,000 of taxable income in 2021. Looking at the chart above, that would put you in the 22% tax bracket. But don’t pay 22% on the entire $50,000. You would pay 10% on the first $9,950, 12% on the chunk of income between $9,951 and $40,525, and then 22% on the rest. Here’s a visual:

Your total tax bill would be about $6,750. Even though you’re in the 22% tax bracket, only around 14% of your income is actually going towards federal taxes. That 14% is called your effective tax rate.

I’ve heard a few people say something along the lines of, “Well, I don’t necessarily want a raise or to make more money this year because I’ll get bumped into a higher tax bracket.”

No. This is flawed thinking. If you want more money in your pocket, it’s always better to make more money.

As I mentioned, when your income increases and bumps you from the 12% tax bracket to the 22% tax bracket, you’re not suddenly paying 22% taxes on all of your income. You’re only paying 22% on the dollars above $40,525. And although you’re now paying more taxes on those dollars, you’re still taking home most of that additional money. This same principle applies to any tax bracket.

If you’re a single filer and make $100,000, you’ll pay almost triple the amount of taxes than if you were making $50,000. However, your take-home pay after those taxes would still be double what it would be if you were only making $50,000.

Remember, 70% of something is always better than 100% of nothing.

Another misconception I want to address is that of tax deductions or “write-offs.” Many people think that because something is tax deductible, it’s essentially free. It’s not.

If something is tax-deductible, it means that you’ll be able to deduct the cost from your taxable income. This will provide a small tax break, but it won’t make the purchase free. Depending on your tax bracket, a tax deduction could make a purchase something like 25% off, but that still means it’s 75% “on”.

For example, let’s say you’re in the 12% tax bracket and you give $5,000 to your local church. Donations to charities are tax-deductible so that $5,000 donation would save you $600 in taxes. Which is awesome if you were planning on giving to your church anyway and weren’t doing it for the tax break.

But if your goal was to preserve as much money as possible and you were donating only for the tax savings, you’d be better off keeping the $5,000 and simply paying the 12% tax bill. In this scenario, you’d keep $4,400 in your pocket instead of losing $4,400 by donating it.

Tax deductions are great for necessary expenses in your life or in your business, but if you’re buying a piece of equipment or donating to charity solely for the tax deduction, it doesn’t make financial sense. The more deductions you take, the less take-home pay you’ll have.

I hope this information is helpful.

It’s important to keep in mind that while tax implications should be taken into account when making financial decisions, they shouldn’t be the determining factor. Just because there’s no state tax in Texas does not mean that everyone should uproot their life and move there. Don’t let the tax tail wag the decision-making dog.

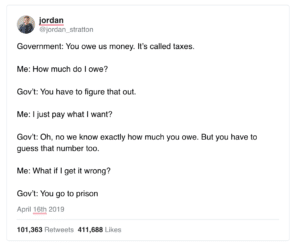

I want to end with a tweet that I see pop up every year around tax season:

Thanks for reading!