Last week my two one-year-old boys came down with a cold. This is their first experience with being sick and they didn’t really know how to cope with not being able to breathe through their noses. For two nights in a row, they would take turns waking up every other hour crying with a clogged nose. And each time we would have to get up to help them unclog their nose and put them back to sleep before the other brother woke up a little while later with the same issue.

Needless to say, no one in our family got much sleep for a few nights.

On Friday afternoon, after I finished up at work for the day, it was my turn to watch the boys as my wife took a much-needed nap. Knowing that cooking a meal wasn’t going to be in the cards for us that night, I packed up the boys and went to grab some quesabirria tacos at one of our favorite local spots to bring home for dinner.

As I was about to pay for my order a man stepped in, possibly having sympathy for a dad holding two car seats looking a bit tired, and insisted on paying for our meal.

It was an extremely kind gesture made even more meaningful given the past few days of exhausting parenting.

We then sat together as we waited for our food to be prepared and struck up a conversation. He asked what I do for work and I told him I’m a financial advisor. Unprompted, he began to tell me about his journey to financial freedom. He started by saying:

“Well, I got very very lucky. I just so happened to be in the right place at the right time.”

He went on to tell me he’s worked for the Union Pacific Railroad his whole career. But in 2009 after the housing market crash, he had just been given inheritance money that he was sitting on and decided to buy up a bunch of foreclosed houses for insanely cheap prices.

As we know, the housing market has been on a tear over the past decade and so this one moment is what has provided almost all of his wealth. Now that his 6 kids are out of the house, he still works for Union Pacific Railroad but travels across the United States in a motorhome with his wife.

I was surprised to hear him talk so candidly and introspectively about how he built his wealth.

From my experience on Twitter (I guess it’s called X now), I thought bragging about your own intelligence and foresight after you made a great investment was a requirement. Like, I assumed there was a whole chapter on self-congratulation in the manual that gets handed out when you make an investment.

When he finally got up to get his food, his last remark to me was:

“Anyway, I feel like I’ve been very blessed in my life so whenever I go out to eat I try to pay it forward in some small way. Good luck with the twins, you’re going to need it!”

His comment reminded me of something I’ve heard Morgan Housel say:

“The luckier you are, the nicer you should be.”

The role of luck in our lives can be a tricky thing to talk about. For the successful, attributing success to luck hurts their ego, and for the unsuccessful, the absence of luck is an easy excuse to fall back on.

Obviously, luck isn’t everything. Talent, passion, discipline, and hard work matter a lot. But these attributes are usually the minimum requirement for being successful—not a guarantee.

Let’s look at the stock market as an example. Much like my newfound friend at the quesabirria taco shop, the year you were born and consequently, the year you start investing will likely have a huge impact on your investment returns.

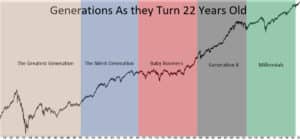

The following chart shows what the stock market was doing when each generation turned 22, the age when most start investing. As you can see, each generation has to deal with different market conditions.

If you had invested from 1960-1980 and beaten the market by 5% each year, you would have made less money than if you had invested from 1980-2000 and underperformed the market by 5% a year.

I’ll end by quoting Morgan Housel again:

“When most people experience bad times they consider it risk – the idea that a force outside of their control influenced outcomes more than anything they did intentionally.

Rarely is that logic turned around.

Because what’s the opposite of risk? Luck. And what is luck? The idea that a force outside of their control influenced outcomes more than anything they did intentionally.

And there are no easy answers on how to manage [luck]. There are so many things in life where distinguishing between sustainable momentum and temporary luck is only known with hindsight.

Maybe the broadest way to protect yourself is the simple rule that the luckier you are, the nicer you should be.

That’s probably the best – or only – way to guard against entitlement, which is the main thing that blindsides you when luck turns the other way.”

Thanks for reading!