As I write this, the U.S. stock market is taking a small tumble, and the internet seems to be in a collective panic. If you’re looking for some stock market material, you can check out these two posts that I wrote back-to-back a couple of weeks ago. The information is still pertinent. And I’ll likely revisit some stock market stuff next week.

But today, I wanted to write about something I get more complaints about than any other finance topic—more than market corrections, inflation, budgeting, debt, you name it.

Taxes.

The annual April 15th tax deadline is coming up next week, and for most, preparing and filing taxes each and every year is a plug-your-nose-and-get-it-over-with type of chore.

Surveys show that 60% of Americans believe they pay too much in taxes. In an age where it feels we can’t agree on anything, a hatred for paying taxes is something that unites us all.

What’s interesting is that 60% of Americans also mistakenly believe that the middle class shoulders the highest tax burden. This highlights a discrepancy I see often between how many people complain about taxes compared to how many people understand how taxes work.

The average taxpayer in America pays around $14,300 in federal income taxes, with an average tax rate of about 15%. But it’s the top 25% of earners that pay 90% of the nation’s taxes, while the bottom 50% account for only about 2%.

The top 1% have an average tax rate of about 26%, while the top 50% only pay 16% of their income toward taxes, and the bottom 50% pay a meager 3%.

Now, before the thought crosses someone’s mind that it might be better to stay in a lower income range so you can pay less in taxes, stop it. You should want to pay a lot of taxes. That means you’re making a lot of money.

Every single person in the bottom 50% of income earners would gladly switch places with someone in the top 1% and jump for joy at their increased tax rate.

I do think it’s easier to hate things we don’t fully understand. And I’ve spoken with plenty of people who don’t quite understand how federal income taxes work, so I think it’s helpful to briefly review how income taxes are calculated.

Does an explanation of income tax brackets make it less painful to pay taxes? Of course not. But I do think it’s important to know how our tax system works.

The U.S. has what’s called a progressive tax system, which is just a fancy way of saying that as your income increases, it’ll be taxed at a higher rate. The government decides how much tax you owe by dividing your taxable income into chunks or tax brackets.

Currently, there are seven tax brackets for ordinary income: 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%. Here are the 2024 tax brackets (for taxes due in April 2025) and their corresponding income ranges:

The most important thing to understand about tax brackets is that being “in” a certain bracket doesn’t mean you pay that tax rate on all of your income. Each chunk of your income gets taxed at the corresponding rate.

For example:

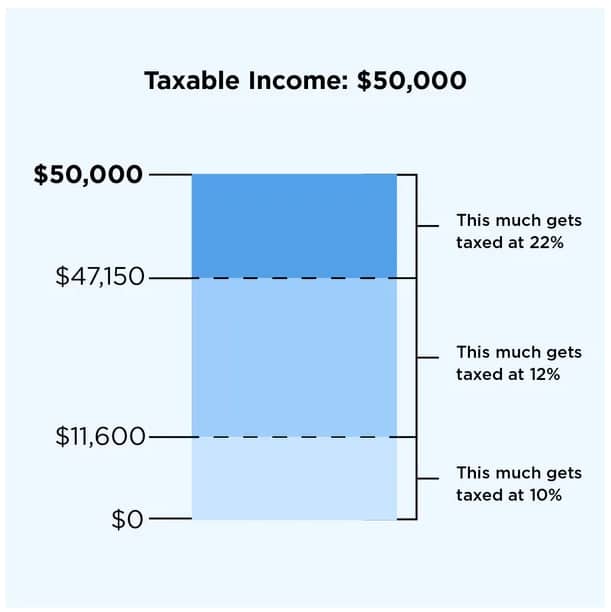

Let’s say you’re a single filer and you had $50,000 of taxable income in 2024. Looking at the chart above, that would put you in the 22% tax bracket. But you don’t pay 22% on the entire $50,000. You would pay 10% on the first $11,600, 12% on the chunk of income between $11,601 and $47,150, and then 22% on the rest. Here’s a visual:

Your total tax bill would be $6,053. So even though you’re in the 22% tax bracket, only around 12% of your income is actually going towards federal taxes. That 12% is called your effective tax rate.

On numerous occasions, I’ve heard people say something along the lines of, “Well, I don’t necessarily want a raise or to make more money this year because I’ll just get bumped into a higher tax bracket.”

This is flawed thinking. If you want more money in your pocket, it’s always better to make more money.

When your income increases and bumps you from the 12% tax bracket to the 22% tax bracket, you’re not suddenly paying 22% taxes on all of your income. You’re only paying 22% on the dollars above $47,150. And even though you’re now paying more taxes on those dollars, you’re still taking home most of that additional money.

If you’re a single filer and make $100,000, you’ll pay triple the amount of taxes than if you were making $50,000. However, your take-home pay after those taxes would still be about double what it would be if you were only making $50,000.

Remember, 70% of something is always better than 100% of nothing.

Another misconception I quickly want to address is that of tax deductions or “write-offs.” Just because something is tax-deductible does not mean it’s free.

Seinfeld and Kramer about write-off

If something is tax-deductible, it means that you’ll be able to deduct the cost from your taxable income. This provides a small tax break, but it doesn’t make the purchase free. Depending on your tax bracket, a tax deduction could make a purchase something like 25% off, but that still means it’s 75% “on”.

For example, let’s say you’re in the 12% tax bracket and you give $5,000 to your local church. Donations to charities are tax-deductible, so that $5,000 donation would save you $600 in taxes. Which is great if you were planning on giving to your church anyway and weren’t doing it for the tax break.

But if your goal was to preserve as much money as possible and you were donating only for the tax savings, you’d be better off keeping the $5,000 and simply paying the 12% tax bill. In this scenario, you’d keep $4,400 in your pocket instead of losing $4,400 by donating it.

Tax deductions are great for necessary expenses in your life or in your business, but if you’re buying a piece of equipment or donating to charity solely for the tax deduction, it doesn’t make financial sense.

I see this all the time with business owners. The goal of starting the business is to make a profit. Then, once they start making a profit and their quarterly tax payments increase, they desperately want to pay less in taxes. But paying less in taxes typically requires a reduction in take-home pay. Tax strategy and planning are important, but the goal isn’t to pay fewer taxes; the goal is profit.

I hope this information is helpful.

Keep in mind that while tax implications should be taken into account when making financial decisions, they shouldn’t be the determining factor. Just because there’s no state tax in Texas does not mean that everyone should uproot their life and move there. Don’t let the tax tail wag the decision-making dog.

Thanks for reading!

Jake Elm, CFP® is a financial advisor at Dentist Advisors. Jake a graduate of Utah Valley University’s nationally ranked Personal Financial Planning program. As a financial advisor at Dentist Advisors, he provides dentists with fiduciary guidance related to investments, debt, savings, taxes, and insurance. Learn more about Jake.</em